The cinema was the major entertainment of the early 20th century: picture theatres were comfortable, respectable and fun.

By 1911, when the department-store owner Marcus Clark built the New York Picture Theatre, Sydney had 14 such dedicated buildings, and there was also a thriving film industry aiming squarely at a local audience with a focus on the convict or bushranging past, such as The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), Robbery Under Arms (1907), For the Term of his Natural Life (1908), Captain Midnight and Captain Starlight (both 1911). Although these were so popular, in 1912, the NSW government censorship banned films “representing scenes such as would have a demoralising effect on young persons, or of successful crime, such as bushranging, robberies, and other acts of lawlessness”!

In building the New York Theatre in The Rocks in 1911, Clarke was aiming at the patronage of families expected to move into the proposed new housing blocks that the NSW Government was planning for the area. The State government’s massive urban renewal project for The Rocks, following the Bubonic Plague scare of 1900, was never fully achieved. The name New York evoked the wealth, excitement, and novelty of that city, but in fact, the theatre was called after the adjoining New York Hotel, a local institution, rebuilt in 1906. The main selling points of the new picture theatre were modernity, grandeur and the wonders of electricity:

The crowning feature of the front and lobby is the grand waterfall stairway, built entirely of plate glass and marble, and down which flows every day 45,000 gallons of water, giving the effect of a grand cascade. This waterfall is operated by an electrically-driven pump, which pours out the water at the rate of 78 gallons per minute. The effect is enhanced by over 100 electric lights buried in the glass and water. The lighting scheme is so arranged that a blaze of light crowns the theatre at all times, and is furnished by the company's own electrical plant. (SMH 19 Dec 1911, p13)

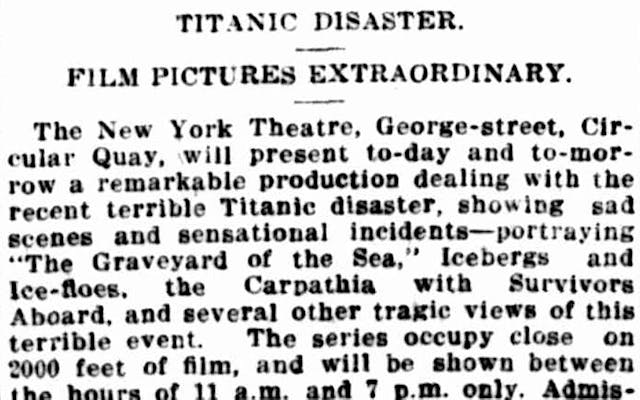

The cinema was an ideal vehicle for sharing news and film-makers were not slow to capitalise on the disaster of the day; a presentation of newsreels subsequent to the sinking of the Titanic which included films of The Graveyard of the Sea, Icebergs and Ice-floes and the Carpathia with Survivors Aboard.

By 1932, the weekly audience worldwide was an astonishing 183 million people, of whom over 90 million were in the United States. Though Australia had only a small industry, there were runaway successes, with the ‘talkie’ version of The Sentimental Bloke and On our Selection.

Film and slides of Mawson’s expedition to the Antarctic were shown during a fund-raising lecture attended by the Governor, Sir Philip Game:

The one ‘talkie’ in the series of films was of Sir Douglas Mawson reading a proclamation annexing to Great Britain a large area of newly-discovered land, and as the Union Jack was hoisted the audience applauded. Penguins were seen fighting, there was a ‘close-up’ of a sea-elephant chasing a member of the expedition and there was a view of what Dr Ingram described as ‘the Bondi of the Antarctic’ – a long beach on Macquarie Island, where thousands of penguins sun-baked, dived, swam, and shot the breakers, apparently with all the enjoyment of Sydneysiders on a hot summer day. (SMH 4 Oct 1932, p9)

In 1931, the theatre had been renamed The Bridge, to mark the anticipated opening of the Harbour Bridge and advertised itself as ‘the home of Continental film’, pitching itself at a niche market. At a time when the local area was caught up in the Great Depression with at least 30% of the male population unemployed, films of this sort had little mass appeal and people flocked to escapist American musicals and romances. In addition, the New South Wales Government was forced to legislate for a 5% Australian content through the NSW Cinematograph Films (Australian Quota) Act of 1935. Whatever the causes of failure, the New York Theatre building was up for lease by mid-1934 and closed in 1935. The forlorn and forgotten building was demolished in 1949 to make way for the railway bridge over George Street to Circular Quay Station.