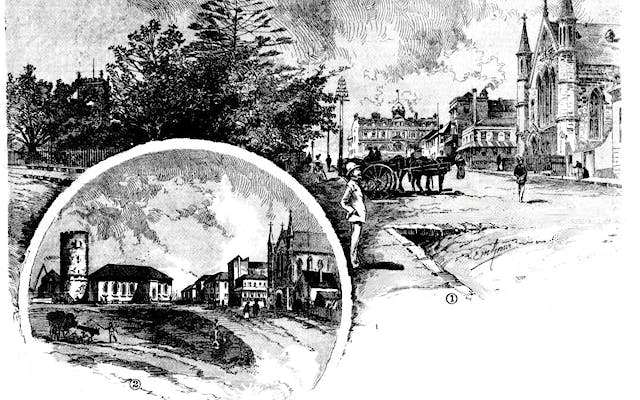

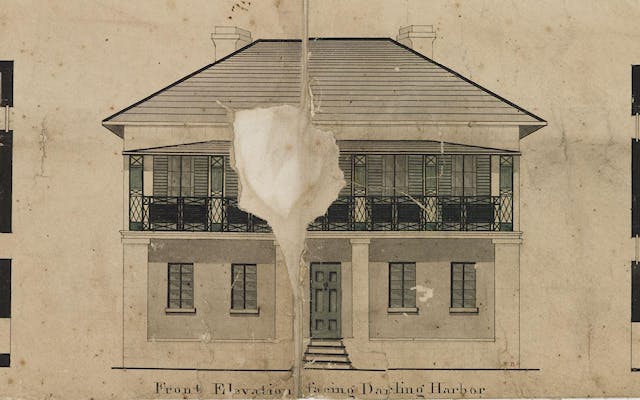

The Rocks/ Tallawoladah was the site of Australia's first European settlement in 1788. As the preface to modern Australia's story, The Rocks played stage to the colony's first residential neighbourhood, along with the initial bakehouse, hospital, and pub.

Inextricable from this history are the lives of the working-class people who lived here for generations. The area was home to an eclectic mix of convicts, ex-convicts, sailors, and dockworkers, all of whom contributed to its unique character. The Rocks came to be seen by social historians as the place that not only marked the beginning of modern Australia’s history, but also the formation of its character [1].

At the time of the 1960’s, The Rocks was still home to multi-generational families, many of whom could trace their lineage back to the first European settlement. Known colloquially as ‘battlers’ for their hardworking lifestyles, these families were largely made up of dockworkers, maritime workers, factory staff, and the labour force behind Sydney’s booming trade industry.

Nita McRae, the leader of The Rocks Residents Action Group (RRAG), argued that what truly set The Rocks apart was the community. “The uniqueness of the area is the people who live in the historic buildings with all their past generations of ancestors who lived and died here,” McRae said.

These communities comprised the very essence of The Rocks that no development could manufacture. They were also prepared to fiercely resist the proposed destruction of their homes in an event that would come to be called 'The Battle for The Rocks.'

A New Plan for The Rocks

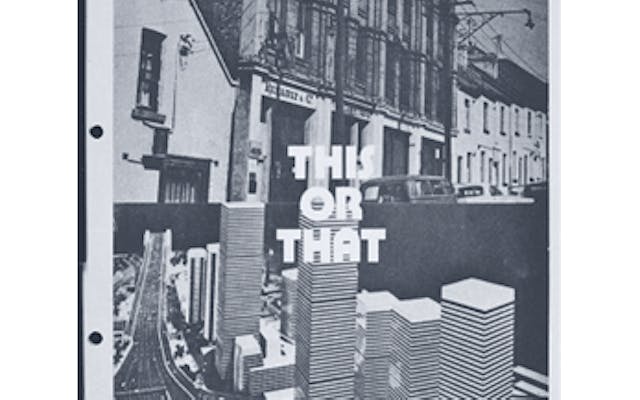

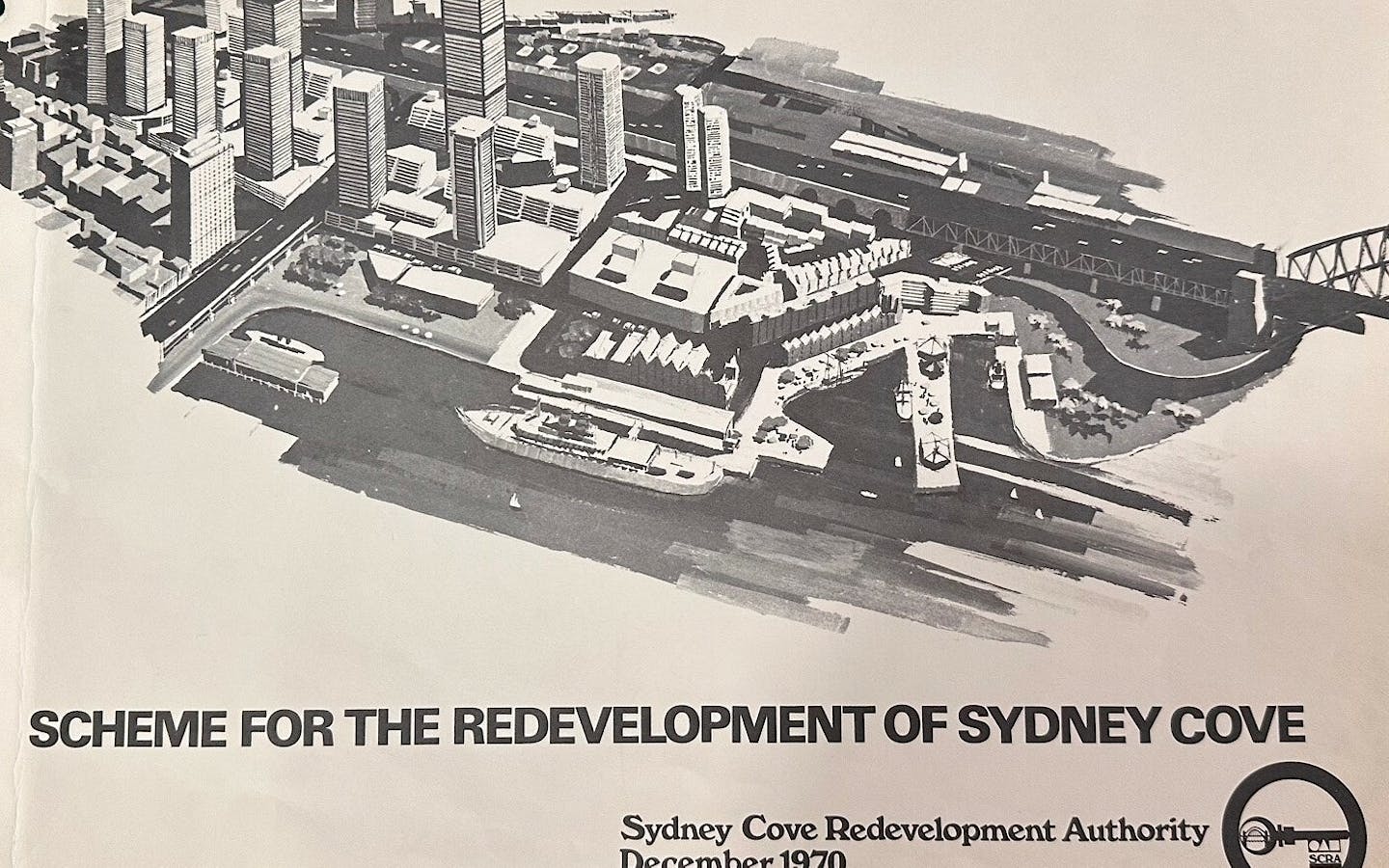

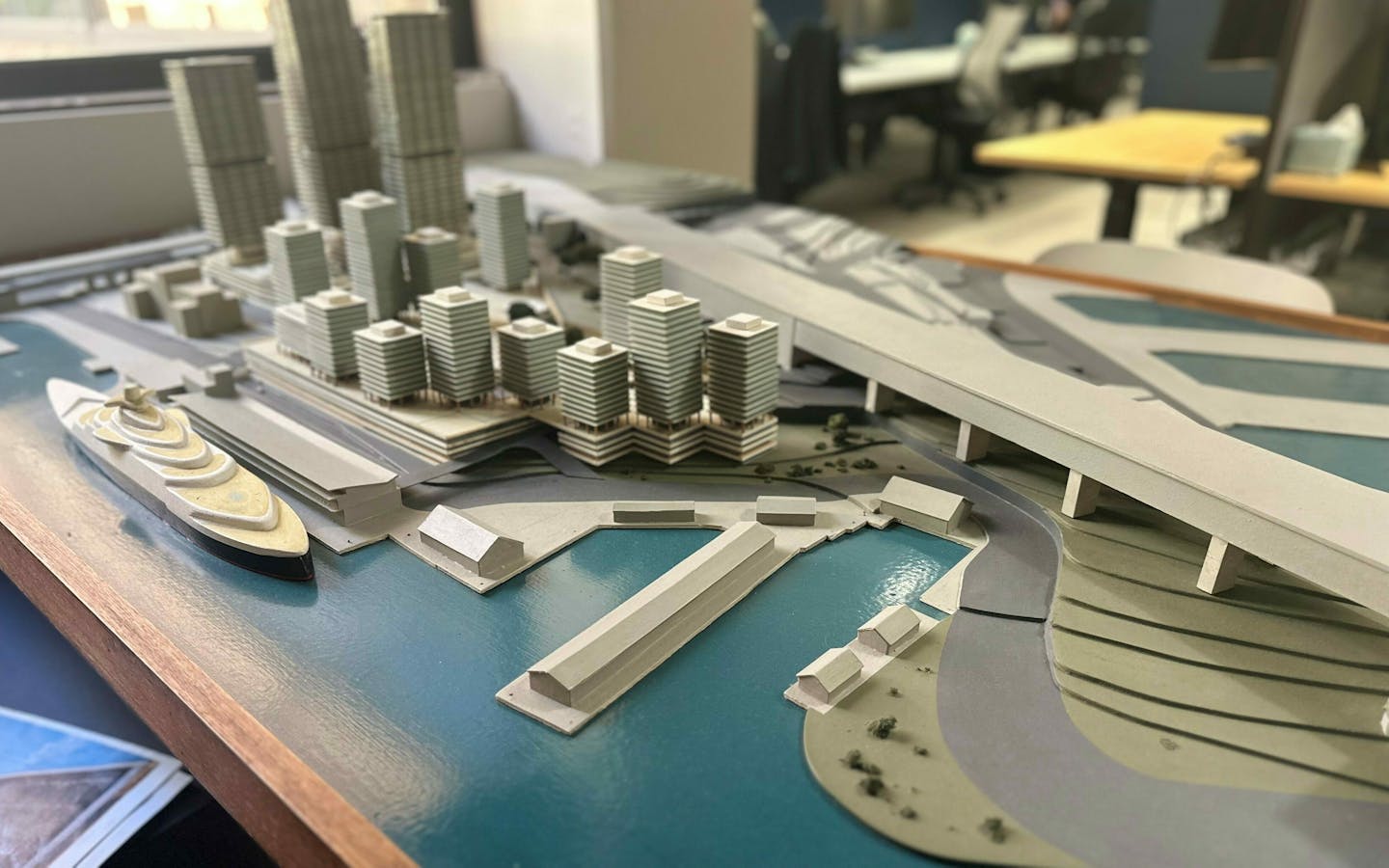

During the 1960s, Sydney was undergoing a huge commercial boom fuelled by the Liberal Premier Robert Askin, who saw redevelopment of historic sites, working class neighbourhoods and green spaces as opportunities for profit. With its proximity to the CBD and public ownership, The Rocks quickly captured the government's interest. In 1970, The Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA) was established to deliver the $500 million redevelopment scheme modified in 1967 by Sir John Overall from an earlier proposal. The scheme, which equated to approximately $6.5 billion today, would have seen The Rocks replaced by high-rise office towers, retail and commercial space, luxury hotels and apartments, and underground car parks.

The redevelopment scheme included a $1 million block of flats and no housing that the locals would be able to afford. After a token exhibition, its plans were promptly authorised without consultation with the locals, nor the people of Sydney in general. Rumours of impending evictions and loss of tenants’ rights led swiftly to the formation of The Rocks Resident Action Group (RRAG), led by Nita McRae.

Illustrating the callous disregard for public sentiment during this period, G.J. Dusseldorp, then chairman of Lendlease, remarked to a group of housing leaders in 1968 that the industry "knows little about the desires of the people and cares less.” Premier Askin labelled The Rocks as a “depressing area," and declared it unsuitable as an entry point into Sydney [2].

The RRAG lobbied the government for a year before seeking support from the NSW Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) who imposed a green ban on The Rocks in 1971.

The Green Bans

The NSW Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) was the first worldwide to introduce the concept of green bans. In 1970 the BLF, led by Jack Mundey, Joe Owens, and Bob Pringle, sought to create a ‘new concept of unionism’ whereby workers had the right to refuse labour used in harmful ways. This was an era of heightened political consciousness, with burgeoning movements for women’s equal pay, indigenous land rights, and anti-war sentiments. The stage was set for a broad base of support for ecological awareness.

The green bans applied to projects which encroached on public green open spaces, proposed demolition of existing public housing, or the replacement of older, historic buildings with modern high-rises. Mundey proclaimed, “We would rather build urgently required hospitals, schools, other public utilities, we well as high-quality flats and houses - provided they are designed with adequate concern for the environment, rather than ugly unimaginative architecturally bankrupt blocks of concrete and glass offices” [3].

The first green ban was placed in 1971 when residents of Hunter's Hill sought the BLF’s help in saving Kelly’s Bush, an untouched area of natural bushland threatened with private development. Its success sparked a flood of similar requests to the BLF.

Unions should be involved in ‘quality of life’ issues as well as the traditional areas of seeking better wages and conditions. What is the good of fighting to improve wages and conditions if we are going to choke to death in polluted and plan-less cities? Jack Mundey, 2nd November 1973

A People’s Plan

The Battle for The Rocks differed markedly from that of Kelly’s Bush due to its involvement with a significant NSW statutory authority instead of a private developer. Unlike Kelly’s Bush, the focal point was not environmental concerns but rather the welfare and housing requirements of numerous low-income public housing tenants. Consequently, the campaign needed to take a fundamentally different approach.

The green ban gave The Rocks Resident Action Group time to strategise and formulate their own counterproposal to the SCRA Scheme. Assisted by a cadre of supportive professionals, they established The Rocks People’s Plan Committee. Their goal was to keep the current residents in place, particularly those with deep-rooted ties to the area, and to empower the community by giving them a voice in future proposals and the option to reject. They aimed to safeguard The Rocks as a residential and historically significant area distinct from the CBD.

Collaborating with architects such as Neville Gruzman, who had personal ties to the area, they crafted a 'people's plan' in 1973. This plan stood in opposition to government apathy and put forth viable modifications, with a focus on reintegrating residents, establishing cultural hubs, and preserving the area's history.

Stopping The Wrecking Ball

In August 1973, the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority announced plans for a $1 million low-rise apartment block on Playfair Street. The site was home to Playfair’s Garage, a rare industrial relic from the twentieth century, as well as former workshops. Dating back to the 1850s, the collection of buildings served blacksmiths and coppersmiths for shipping needs and later functioned as a food relief depot during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Owen Magee, SCRA’s director, dismissed the site as a 'derelict garage with no value whatsoever' [4]. Nita McRae and the RRAG quickly mobilised the BLF and other action groups.

It is important to note that while the movement’s leaders recognised the need for heritage listings to preserve The Rocks and other sites from demolition -The BLF refused to demolish any of the 1,700 buildings in NSW recommended for preservation by the National Trust- their chief focus was on protecting social and urban rights for the area’s working-class residents.

A representative of Silverton Ltd, the company tasked with constructing the apartments, said he envisioned the potential tenants to be ‘Middle-aged women with successful divorces and young executives.’ It was clear that the apartments would not benefit existing tenants and thus, the green ban remained. The RRAG argued that no-one currently living in The Rocks could afford the rent for these apartments.

Mundey articulated the union's stance unequivocally in August: "My federation will lift its ban when the residents are satisfied with what is being put forward by the authority" [5]. Despite the green ban, non-union labour had started demolishing the building. It was time to act.

"What we want are concrete assurances that 167 families who will be affected by the redevelopment will not be thrown out of their homes with nowhere else to go. Until we get those assurances the ban will stay on." Bob Pringle, President of NSWBLF (Daily Mirror, 8 January 1972)

The Battle Unfolds

Thursday 18th October 1973

The BLF effectively brought demolition to a halt by organising a protest that saw over 100 labourers walk off their job sites. Initially, Silverton’s director snubbed the ban but later agreed to a 24-hour truce pending negotiations. Anticipating that demolition might resume, delegates from seven sites across the city agreed to monitor the situation at Playfair Street. Should the demolition go ahead, the BLF was prepared to occupy the site.

Friday 19th October 1973

As expected, demolition continued. The labourers assembled for a strike meeting before marching over to the Playfair site to protest violation of the green ban, where a contingent of 20 police officers were in wait. They then proceeded to the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority office for answers.

Joe Owens warned that if demolition continued as scheduled on Monday, the site would be occupied again. Magee, the SCRA’s director, gave his assurance that no further work would take place. However, he later said he would not concede to ‘mob violence’ and accused the BLF of putting their staff and the public at risk.

Monday 22nd October 1973

At 8:30 a.m. Monday, Joe Owens informed attendees that he had received word that SCRA had halted work due to the occupation threat. All agreed to reconvene if any other bans were violated, allowing builders and labourers to return to work. Later, Owens and Pringle met with Mr. Hills, the state opposition leader, urging the inclusion of a strategy in the Labour Party's policy to preserve Sydney's historic areas for affordable housing.

Tuesday 23rd October 1973

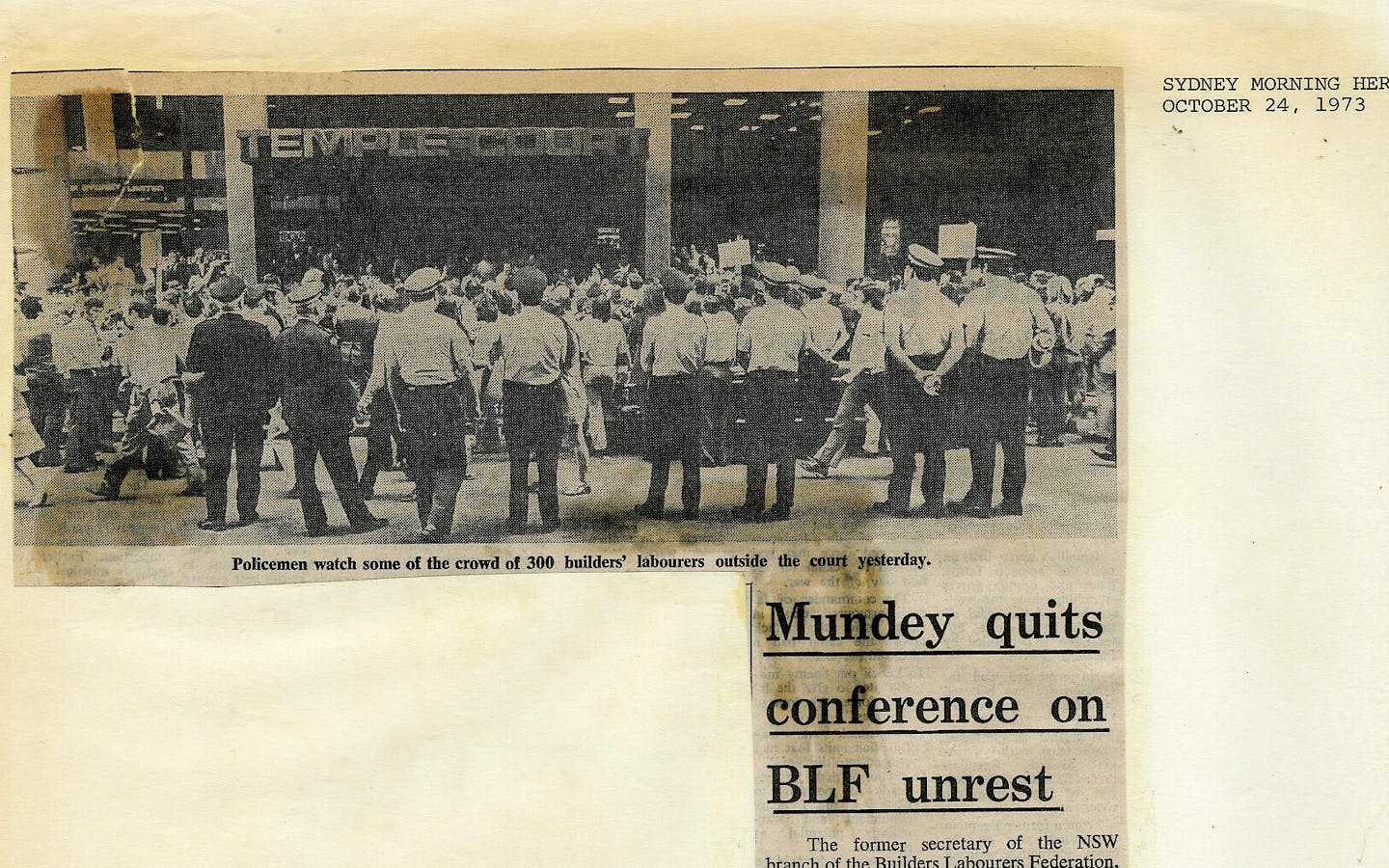

Mr Justice Aird presided over a Conciliation Commission conference on Tuesday. Sixteen members of the Federation's Federal Executive, along with a representative from the Master Builders Association (MBA), were called to attend. The Commission implied the threat of deregistration if the green ban wasn't lifted. Mundey opposed conducting the meeting without other union members or local resident representation, emphasising that it was a matter of social importance. He also assured the 500 union members and resident action groups outside the court that they wouldn't be forced into compliance against their will.

Wednesday 24th October 1973

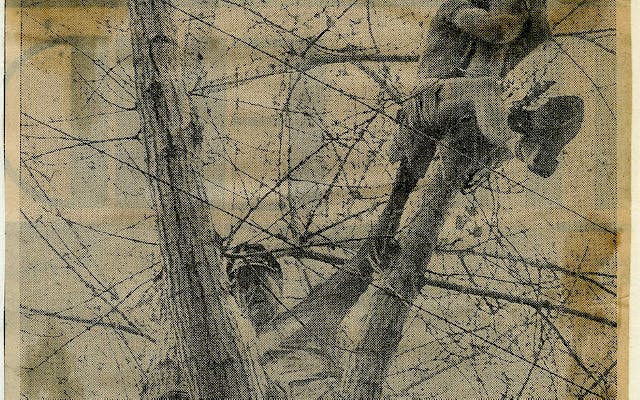

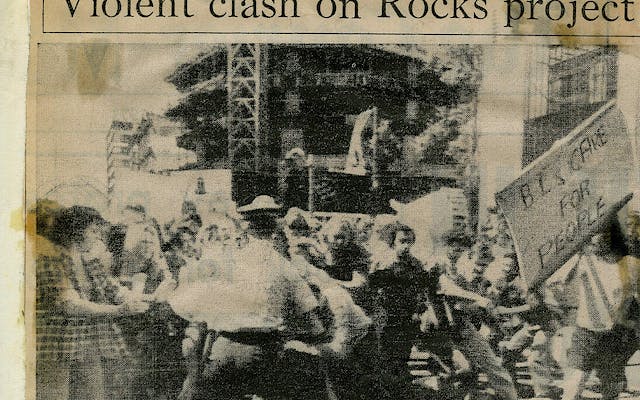

By the first light of dawn, a diverse ensemble of approximately 100 individuals began assembling at the Playfair Street site. Comprising union executives, students, and members of resident action groups from The Rocks, Woolloomooloo, and Kings Cross, they were equipped for a day-long nonviolent sit-in with food, beverages and musical instruments. To secure their position, they improvised barricades using oil barrels, corrugated iron sheets, and hoses. A few even climbed up into trees.

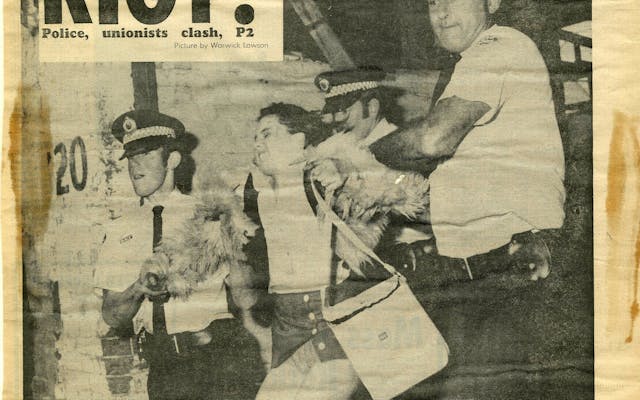

As 7 a.m. approached, the first of the law enforcement agents began to arrive. By 8 a.m., a contingent of 60 police officers armed with tear gas initiated the arduous task of dismantling the makeshift encampment. The crowd, though physically dispersed, maintained a vocal presence, chanting 'Keep The Rocks for the people!' as they were systematically and forcibly removed.

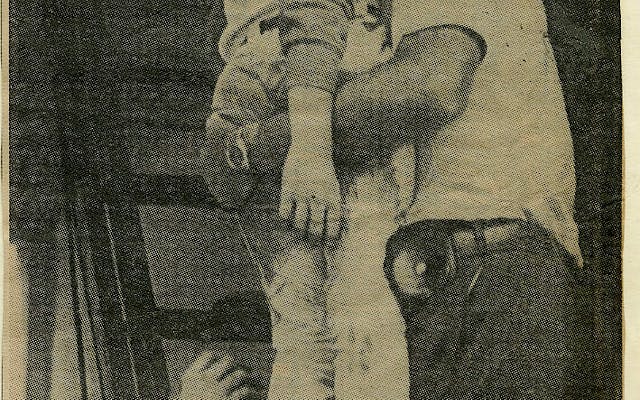

The tense standoff continued for hours, concluding around 7:30 p.m. when the last resolute protester was apprehended. Sequestered in a tree for nearly nine hours, this individual identified himself to the police as Elvis.

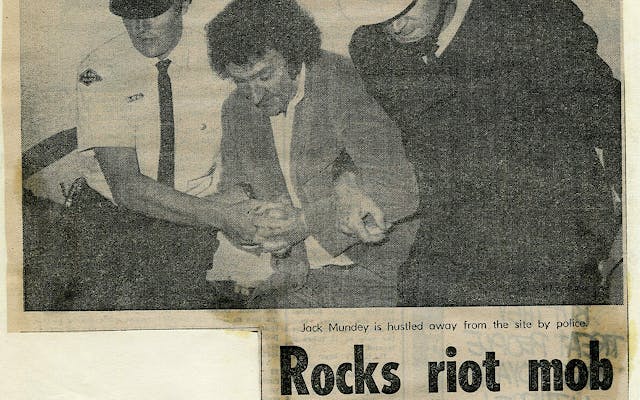

54 demonstrators—including BLF leaders Jack Mundey, Joe Owens, and Bob Pringle—were charged with trespassing. Mundey, casually escorted by three policemen, seemed unfazed. His clasped hands and subtle grin becoming an iconic representation of the Battle for The Rocks. After an attendee collapsed amidst the day's chaos, Owens declared his intent to file complaints about police conduct.

The day illustrated the determination of a community that refused to disappear without a fight. It also raised ethical questions about the length authorities were willing to go to quash dissent, all in the name of development.

Thursday 25th October 1973

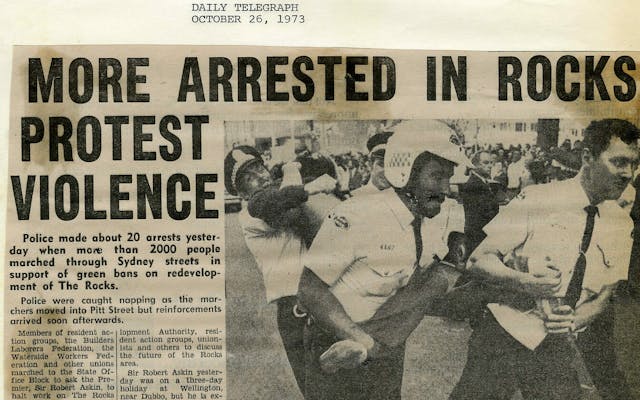

Undeterred by the previous day’s setbacks, protesters reconvened at Foundation Park, ready to march in a unified voice. Following stirring speeches by Pringle and Mundey, the crowd was raring to go. With arms linked and voices raised in a unified chant of 'green bans, Askin out,' they set off on a spirited march up Pitt and Hunter Streets.

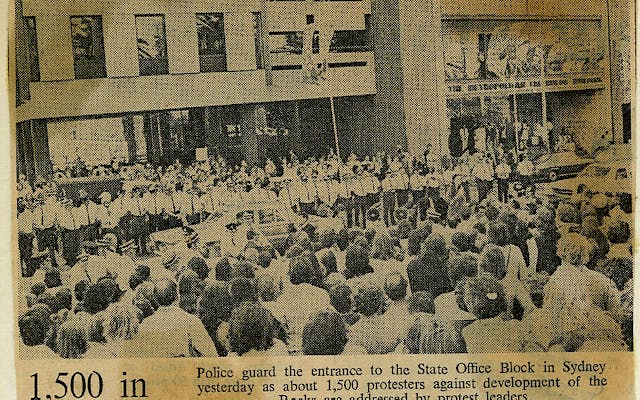

A seven-piece jazz band led the way, providing a rousing soundtrack to the procession. Marching behind a banner that read "B.L. (Builders Labourers) Care for People," the protesters marched towards the state office block, where they demanded an audience with Premier Askin.

Upon arrival, they were met with a wall of furious police officers blocking the entrance to the building. After a heated exchange, a delegation of eight, including Mundey and resident leader Nita McRae, spoke with the Premier's private secretary. They were informed that Askin was on holiday and official discussions would take place the following week.

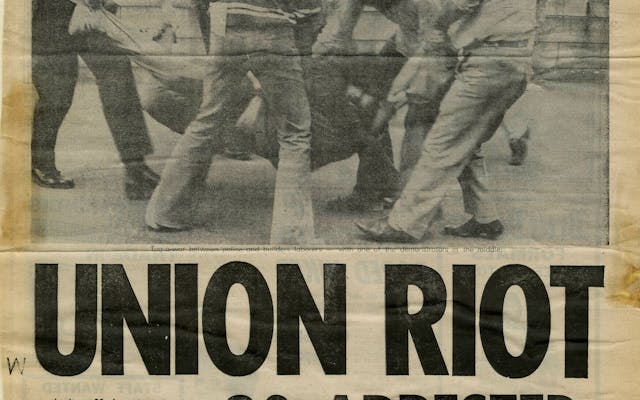

The day did not end peacefully. More arrests were made outside, including the BLF President, Bob Pringle. Joe Owens tried to restore order by urging the crowd to make their way to Macquarie Street Park, where tensions escalated into further confrontations with the police as they attempted to move a union car from the area.

Backlash

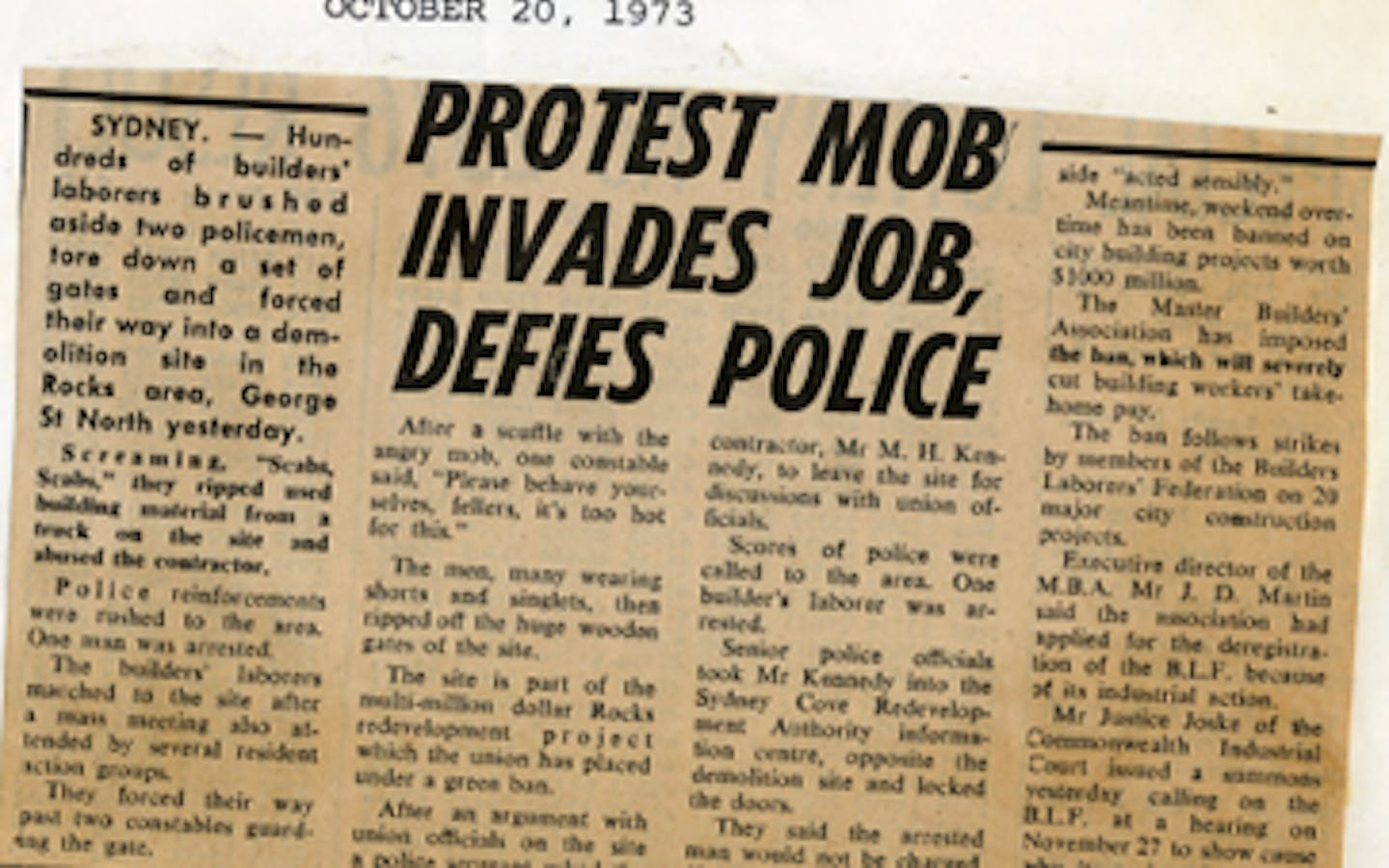

Although the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority had promised that non-union labourers—commonly referred to as 'scabs'—would no longer return to the occupied sites, they repeatedly did so. Throughout the two-week period of demonstrations and meetings, the BLF faced constant opposition from the police, despite their efforts to avoid such confrontations.

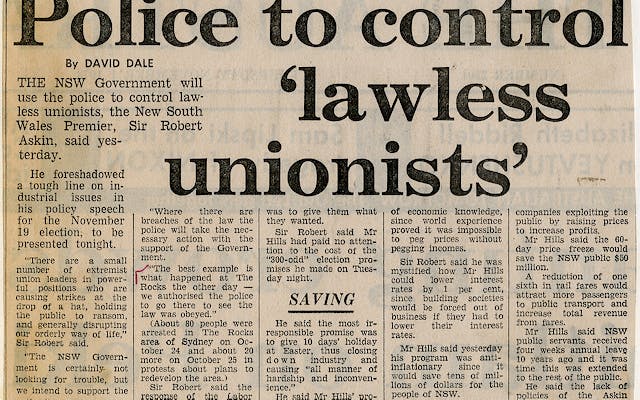

The response from the media to the protests was immediate and scathing. Sydney's newspapers consistently featured headlines depicting the peaceful demonstrators as a 'riot mob' violently attacking police.

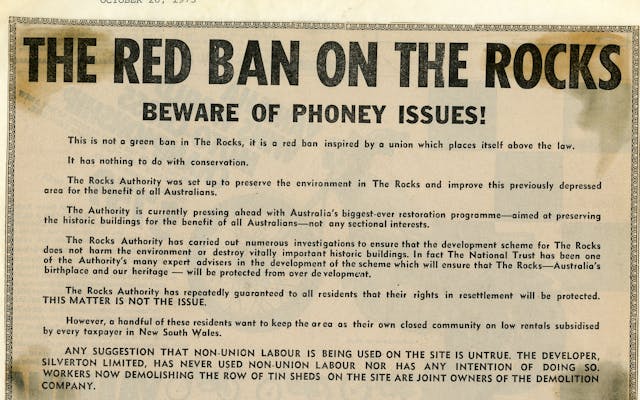

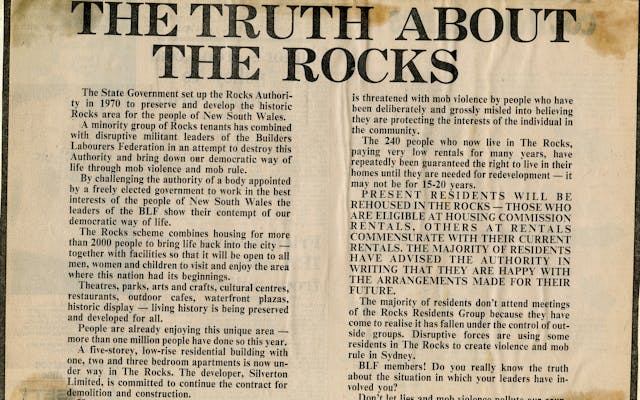

The SCRA ran extensive newspaper advertisements accusing the union of hindering essential projects desired by the public. They also implied that the residents simply wanted to pay low rent at the taxpayers' expense. In response, the union accused Askin of deliberately inciting violence to gain political power. Later in his policy speech, Askin labelled the union leaders as ‘extremists’ and vowed to take a tough stance.

Fortunately, support from other unions and the public started to grow. It became evident that the battlers for The Rocks were not going to back down. Smear campaigns against them had failed and attempts at bribery (to both the union and the residents) were rejected. The tide was noticeably shifting in their favour. The green ban remained on The Rocks. The resistance ironclad.

The Triumph of Resilience

Perhaps sensing the changing winds, and with $5 billion worth of development being held up by the ban, the SCRA eventually capitulated. They began to emphasise their efforts to restore historically significant buildings and agreed to let the residents stay at housing commission rates.

One journalist quipped that the Builders Labourers Federation had become the most powerful town planning agency in New South Wales [5]. Indeed, the BLF and the residents had not only safeguarded their homes and heritage but also redefined the balance of power in urban development.

From High-Rise Ambitions to Heritage Priorities

The Battle for The Rocks brought about a seismic shift in urban planning philosophy. The Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA) revisited their scheme in 1974. The revised plans echoed a newfound respect for the area's cultural, social, and historical heritage. Skyscrapers would now be limited to south of the Cahill Expressway, while the existing historical fabric to the north was diligently preserved. Notably, Playfair's Garage was spared from the wrecking ball and is now home to The Rocks Square.

Additionally, the SCRA made good on their promise to the residents. The late 1970s saw the construction of Sirius, a striking marvel of brutalist architecture, which remains the only high-rise building in The Rocks. It comprised 79 apartments, equipped with rooftop gardens and communal spaces, designed specifically for families and senior residents. Although the building has since been privatised, and the intended residents are sadly no longer present in the area, it continues to stand as a significant symbol of this historic win.

The success of the green bans had wide-reaching implications not just The Rocks, but for policy-making across New South Wales. The movement's crowning achievements were manifest in a slew of ground-breaking laws. The Environmental Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974 and the New South Wales Heritage Act 1977 set a new standard for heritage conservation and environmental stewardship. Further strengthening the legal framework, the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 and the Land and Environment Court Act 1979 established an ecosystem of checks and balances to prevent hasty or irresponsible developments.

In 1998, when the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority took over the reins, it inherited this evolved approach to planning. Preserving the essence of community-driven policy, the Authority gave weight to public opinion on key issues and continued to prioritise cultural, social, and historical considerations. Their work extended to archaeological explorations that unearthed facets of colonial history.

Today, The Rocks is a vibrant cultural hub, adorned with public art and installations, including a towering portrait of Jack Mundey on Globe Street. The Rocks Discovery Museum showcases the green bans' legacy through exhibits that illuminate the movement's stories and struggles.

A Lasting Legacy

The direct action by residents and union members led to The Rocks earning conservation area status, complete with over 100 heritage-listed items. This landmark accomplishment set the stage for culturally relevant development. The intact buildings, public areas, and parklands in The Rocks stand as concrete evidence of the Battle for The Rocks.

Reflecting on the pivotal events of 24 October 1973, Mundey noted, "That morning's occupation was merely one of numerous actions that collectively preserved The Rocks. The allied forces of citizens and unionists not only halted insensitive developments but also empowered the public in decision-making processes." [6].

Journalist Wendy Bacon, arrested for protesting the WestConnex tollway in 2016, was detained alongside Mundey during the Battle for The Rocks 43 years prior. Bacon emphasises that although activists are often maligned in the present, they have a transformative influence on the future and are frequently vindicated in hindsight [7].

The Rocks serves as a compelling testament to the power of working-class action. It's a tangible reminder that urban development must be balanced with a deep respect for history and community. As we commemorate its 50th anniversary, it's an opportune moment to reflect on the dedication of those involved. Let’s also consider what is important to conserve and advocate for in the decades ahead.

Anna Adey

References

[1] Roddewig RJ. Green Bans. 1978.

[2] Red Flag [Internet]. redflag.org.au. [cited 2023 Sep 27]. Available from: https://redflag.org.au/node/67...

[3] Sydney Morning Herald. 1972 Jan

[4] Sydney Morning Herald. 1972 Jan

[5] Burgmann M, Burgmann V. Green Bans, Red Union - Environmental Activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation. UNSW Press; 1998.

[6] Colman J. The House That Jack Built. NewSouth; 2016.

[7] Bacon W. Our Past, Our Future, My Arrest: Wendy Bacon On Getting Nicked By The Newtown Coppers [Internet]. New Matilda. 2016 [cited 2023 Sep 27]. Available from: https://newmatilda.com/2016/11...