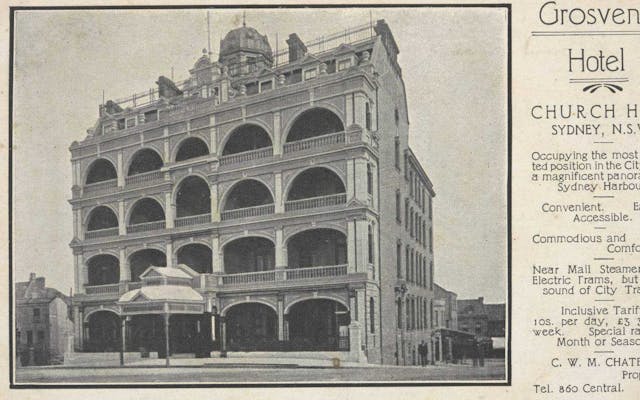

Despite the squalor and social problems associated with The Rocks in the popular mind, there were also patches of splendour and none was more splendid than the Grosvenor Hotel. In its heyday the hotel’s prominence was such that Charlotte Place – named by Governor Macquarie in 1810– was renamed Grosvenor Street.

It was a monumental undertaking, with extensive views, perched high on Church Hill, on the site of a windmill built almost a century earlier. The Grosvenor promised sumptuous world-class elegance to attract the best clientele.

The Sydney Mail on 15 December 1888 provided a detailed description: it was four stories high with a central dome under which was an octagonal smoking room. The view from up there was spectacular:

The city, suburbs, and harbour are spread as a grand panorama around, and whoever once sees the picture will fully realise Sydney's claim to rank as the Queen City of the South.

There was a lift, of course, in the centre of the building, the landing space flanked by staircases and lit by stained glass windows. Walls were wood-paneled throughout. On the top two floors were bedrooms, with communal bathrooms on each floor. All fixtures were of the best quality, with the name of the hotel on all linen, and toilet ware was ‘of cream tint edged with gold’. The two lower stories were public, with an ultra-large dining room on the ground floor. The first floor had two sitting rooms, a family dining room, a ladies’ dining room and a very grand drawing room., with gold and green velvet-covered seats, chandeliers and many mirrors.

Gentlemen were particularly well catered for:

There is every inducement to let the hours slip by, as the spacious lounges or the cosiest of chairs invite one to rest, and when exercise is needed the billiard room, 36 x 40, with three of Alcock's best tables, is not far off. Mr. Whiting points with pardonable pride to this room as 'all Australian.' The furniture is blackwood, and upholstered in leather; the long seats are ranged so as to give onlookers an excellent view; beyond is a little cardroom with Chippendale furniture, and lavatories with the latest appliances for comfort attached.

The [rooftop] smoking room is so cosy that it invites indulgence. An ice-chest is filled with aerated -waters and communication is established with the ground floor, so that a request made there in a speaker's ordinary voice is sufficient to ensure prompt attention from below.

The Grosvenor opened with a splash by hosting two visiting American baseball teams, the All American and the Chicago. The hotel reached its peak under the management of Carlo Chateau, and his son, pioneer aviator Flight Lieutenant Clive Chateau, from 1907 to 1925.

Carlo Waldemar Muller Chateau (1858–1921) was born in Paris and had been a chemist at Copenhagen’s Carlsberg Brewery and an officer in the Danish Hussars before emigrating to Australia in 1884. He worked as a brewer in Bendigo and there met his wife, Edith Brown (1866–1935), born on the Victorian goldfields. Their three sons fought in World War I, notably Clive Chateau (1894–1944), who served with the ANZACs at Gallipoli and joined the Royal Air Force towards the end of the war. In 1919, on his return to Australia, he purchased two planes, became a keen promoter of the aviation industry, and took over the running of the Grosvenor from his father who was ailing.

Carlo may have been ill in 1919, but he was well able to withstand an enraged mob of 700-800 returned soldiers who were demanding to see the Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, who had received a hostile reception during his election speech at Sydney Town Hall, and had quietly slipped back to the Grosvenor. Chateau barred the entrance against the mob trying to force an entry, while staff phoned for police assistance. Clashes with the police then followed before the crowd was charged and dispersed. (Barrier Miner 8 Nov 1919)

When Carlo died in 1921, Clive continued the business for another four years. In 1928, he was actively involved in Kingsford Smith and Ulm’s Trans-Pacific flight from the United States to Australia in the Southern Cross. In that same year the hotel, and some 280 houses surrounding it, disappeared under the wrecker’s ball to clear the way for the approach to the Sydney Harbour Bridge.